Spacetime

Spacetime is a fundamental concept in modern physics that merges the three dimensions of space with the one dimension of time into a single four-dimensional continuum. This framework is essential for understanding the theories of special relativity and general relativity, developed by Albert Einstein in the early 20th century. In classical physics, space and time were treated as separate and absolute entities, but spacetime reveals their interdependence, where the geometry of this continuum is influenced by mass and energy, affecting the motion of objects and the propagation of light.

The idea of spacetime revolutionized our perception of the universe by demonstrating that what we experience as time can vary depending on relative motion and gravitational fields. For instance, clocks tick slower in stronger gravitational fields or at higher speeds, a phenomenon known as time dilation. This unification allows physicists to describe events not just by their spatial location but by their position in this four-dimensional manifold, where the path of an object through spacetime is called its worldline.

Spacetime is not merely a mathematical abstraction; it has profound implications for cosmology, black holes, and the expansion of the universe. In general relativity, spacetime is curved by the presence of matter, and this curvature dictates the laws of gravity as the geodesic motion of objects along the curved paths.

History

The concept of spacetime emerged from efforts to reconcile the principles of electromagnetism with Newtonian mechanics. In the late 19th century, the Michelson-Morley experiment failed to detect the luminiferous aether, prompting Hendrik Lorentz and others to develop transformations that preserved the speed of light invariance. It was Einstein, however, who in 1905 interpreted these transformations as evidence that space and time are relative, leading to special relativity.

The term "spacetime" was coined by Hermann Minkowski in 1908, who formalized it geometrically. Minkowski declared that "Henceforth space by itself, and time by itself, are doomed to fade away into mere shadows, and only a kind of union of the two will preserve an independent reality." This geometric interpretation paved the way for general relativity in 1915, where spacetime becomes dynamic and curved.

Subsequent developments include the work on wormholes by Einstein and Nathan Rosen in 1935, and the prediction of gravitational waves, confirmed in 2015. Quantum field theory and string theory have attempted to quantize spacetime, though a full quantum gravity theory remains elusive. Despite its successes, spacetime has faced criticism from inception, with ongoing debates about its fundamental nature in quantum contexts.

The following table outlines the historical progression of spacetime as a scientific idea.

| Category | Event | Historical Context | Initial Promotion as Science | Emerging Evidence and Sources | Current Status and Impacts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Relativistic Views | Ancient and Newtonian conceptions of absolute space and time | From Aristotle's views on place to Newton's Principia Mathematica (1687), where space and time are fixed arenas for motion. | Promoted in classical mechanics as foundational for planetary motion and terrestrial physics. | Galileo's relativity principle and Maxwell's equations hinted at inconsistencies. | Forms the basis of everyday engineering but superseded by relativity for high speeds and strong fields. |

| Special Relativity | Einstein's 1905 paper on electrodynamics of moving bodies | Crisis in physics due to ether theory failure; Lorentz transformations developed. | Einstein proposed time dilation and length contraction as physical realities, not just mathematical tricks. | Michelson-Morley experiment (1887); invariance of c confirmed theoretically. | Core of particle physics; GPS satellites account for relativistic effects. |

| Minkowski Spacetime | 1908 Cologne lecture by Minkowski | Building on special relativity, geometric reformulation sought. | Introduced four-dimensional manifold with metric signature. | Derived from Lorentz group algebra; interval ds² = -c²dt² + dx² + dy² + dz². | Standard framework for relativistic kinematics and field theories. |

| General Relativity | Einstein's field equations (1915) | Extension to accelerated frames and gravity; equivalence principle. | Gravity as curvature of spacetime; geodesic deviation explains orbits. | Perihelion precession of Mercury (1859 anomaly resolved); Eddington's 1919 eclipse observations. | Describes black holes, cosmology (Big Bang, dark energy); LIGO detections (2015 onward). |

| Quantum Challenges | Attempts at quantum gravity (1920s–present) | Incompatibility between GR and quantum mechanics at Planck scale. | Loop quantum gravity, string theory propose discrete or higher-dimensional spacetime. | Hawking radiation calculations; AdS/CFT correspondence. | Ongoing research; impacts holography, multiverse ideas, but no experimental confirmation yet. |

Mathematical formulation

In special relativity, spacetime is described by the Minkowski metric, a flat pseudo-Euclidean space. The line element is given by

- <math>ds^2 = -c^2 dt^2 + dx^2 + dy^2 + dz^2,</math>

where c is the speed of light, and the signature is (-,+,+,+). Events are points in this space, and the proper time τ along a timelike path is <math>d\tau = \sqrt{-ds^2}/c</math>. The Lorentz group preserves the metric, ensuring the constancy of light speed.

In general relativity, spacetime is a pseudo-Riemannian manifold with metric tensor gμν, and curvature described by the Riemann tensor. The Einstein field equations relate geometry to matter:

- <math>R_{\mu\nu} - \frac{1}{2} R g_{\mu\nu} + \Lambda g_{\mu\nu} = \frac{8\pi G}{c^4} T_{\mu\nu},</math>

where Rμν is the Ricci tensor, R the scalar curvature, Λ the cosmological constant, G Newton's constant, and Tμν the stress-energy tensor. Solutions like the Schwarzschild metric describe black holes, with event horizon at r = 2GM/c².

The geodesic equation, governing free-fall paths, is

- <math>\frac{d^2 x^\lambda}{d\tau^2} + \Gamma^\lambda_{\mu\nu} \frac{d x^\mu}{d\tau} \frac{d x^\nu}{d\tau} = 0,</math>

where Γλμν are Christoffel symbols derived from the metric: <math>\Gamma^\lambda_{\mu\nu} = \frac{1}{2} g^{\lambda\sigma} (\partial_\mu g_{\nu\sigma} + \partial_\nu g_{\mu\sigma} - \partial_\sigma g_{\mu\nu})</math>. Coordinates are often contravariant xμ = (ct, x, y, z), with Greek indices from 0 to 3. Tensors transform under coordinate changes, enabling local inertial frames via the equivalence principle.

For rotating black holes, the Kerr metric extends Schwarzschild:

- <math>ds^2 = -\left(1 - \frac{r_s r}{\rho^2}\right) dt^2 - \frac{2 r_s a r \sin^2\theta}{\rho^2} dt d\phi + \frac{\rho^2}{\Delta} dr^2 + \rho^2 d\theta^2 + \frac{\sin^2\theta}{\rho^2} \left[ (r^2 + a^2)^2 - a^2 r_s r \Delta \sin^2\theta \right] d\phi^2,</math>

with ρ² = r² + a² cos²θ, Δ = r² - r_s r + a², r_s = 2GM/c², and a = J/(Mc), where J is angular momentum.

Properties

Spacetime exhibits causality structure: timelike intervals allow signal transmission slower than light, spacelike faster (impossible), and null for light rays. Closed timelike curves, potential in some solutions like Gödel's universe, raise paradoxes but are avoided in standard models.

The causal structure is determined by the light cone at each event, dividing spacetime into past, future, and elsewhere regions. In curved spacetime, singularities like those in black holes or the Big Bang represent breakdowns where predictability fails.

Topological properties can vary; while usually assumed simply connected, wormholes suggest multiply connected spacetimes, though stability issues persist.

In general relativity

General relativity treats gravity not as a force but as the manifestation of spacetime curvature. Massive bodies warp the manifold, and objects follow geodesics—the straightest possible paths in curved space. This explains phenomena like gravitational lensing, where light bends around massive objects, confirmed by observations of galaxy clusters.

The expanding universe is modeled by the Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker metric, incorporating the cosmological constant for accelerated expansion driven by dark energy. Black holes, solutions to the field equations, feature event horizons beyond which escape is impossible, with Hawking radiation suggesting quantum evaporation over immense timescales.

Gravitational waves, ripples in spacetime propagating at light speed, carry energy and were first directly detected from merging black holes, validating the theory's predictions.

Black holes

Black holes are regions of spacetime where gravity is so intense that nothing, not even light, can escape once it crosses the event horizon—a boundary defined by the Schwarzschild radius r_s = 2GM/c² for non-rotating (Schwarzschild) black holes. Predicted by general relativity in 1916 through Karl Schwarzschild's solution to the field equations, black holes form from the collapse of massive stars or mergers of compact objects.

The interior features a singularity at r=0, where curvature becomes infinite, and spacetime metric diverges. The no-hair theorem states that black holes are characterized solely by mass M, charge Q, and spin J, losing all other information about their formation. For charged black holes, the Reissner-Nordström metric applies:

- <math>ds^2 = -\left(1 - \frac{2GM}{c^2 r} + \frac{G Q^2}{4\pi \epsilon_0 c^4 r^2}\right) c^2 dt^2 + \left(1 - \frac{2GM}{c^2 r} + \frac{G Q^2}{4\pi \epsilon_0 c^4 r^2}\right)^{-1} dr^2 + r^2 d\Omega^2,</math>

where dΩ² = dθ² + sin²θ dφ². Observational evidence includes the 2019 Event Horizon Telescope image of M87*'s shadow and LIGO's detection of binary black hole mergers since 2015, with over 90 events by 2025 confirming inspirals, mergers, and ringdowns matching general relativity predictions.

Black holes challenge classical spacetime with information paradoxes: Hawking radiation, derived from quantum fields in curved spacetime, implies thermal emission at temperature T = ħc³/(8πGMk_B), leading to evaporation but apparent loss of quantum information, resolved in part by holography and entanglement.

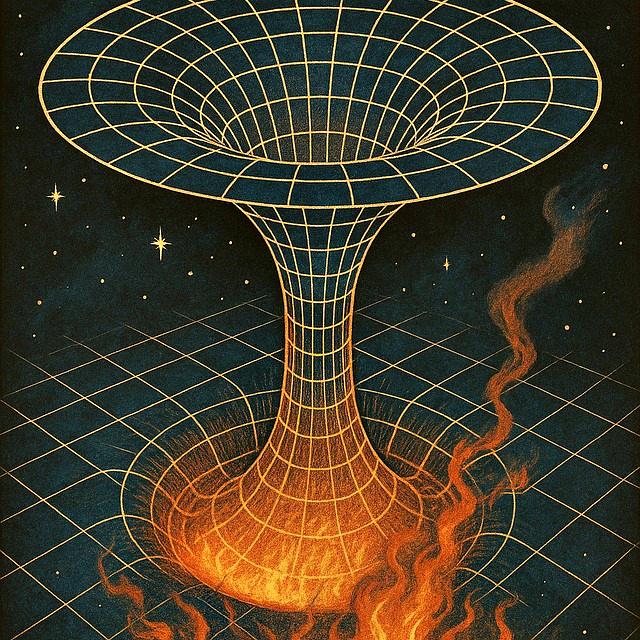

Wormholes

Wormholes, or Einstein-Rosen bridges, are hypothetical topological shortcuts through spacetime, first proposed in 1935 by Einstein and Rosen as solutions linking distant regions via a throat. In the Schwarzschild metric, these are non-traversable, pinching off instantly due to instability.

Traversable wormholes require exotic matter with negative energy density to violate the null energy condition, as in the Morris-Thorne metric:

- <math>ds^2 = -e^{2\Phi(r)} c^2 dt^2 + \left(1 - \frac{b(r)}{r}\right)^{-1} dr^2 + r^2 (d\theta^2 + \sin^2\theta d\phi^2),</math>

where Φ(r) is the redshift function and b(r) the shape function, with b(r_0) = r_0 at the throat radius r_0. Quantum effects like Casimir energy might stabilize them, but macroscopic traversability remains speculative, potentially enabling faster-than-light travel or time machines if closed timelike curves form.

In quantum gravity, wormholes appear in ER=EPR conjecture, linking entanglement (EPR) to geometry (ER), suggesting spacetime connectivity emerges from quantum correlations. Observations are absent, but gravitational wave echoes or microlensing could hint at their existence.

Connection to quantum physics

Spacetime's integration with quantum mechanics poses the central challenge of quantum gravity, as general relativity's smooth manifold conflicts with quantum fluctuations at the Planck scale (l_P ≈ 1.6 × 10^{-35} m, t_P ≈ 5.4 × 10^{-44} s). The "problem of time" arises: quantum mechanics evolves via a time parameter absent in general relativity's diffeomorphism-invariant formulation, leading to the Wheeler-DeWitt equation HΨ = 0, a timeless constraint.

Approaches include loop quantum gravity (LQG), quantizing spacetime into spin networks with discrete area spectrum A = 8πγ l_P² √j(j+1), where γ is the Immirzi parameter and j half-integer spin. String theory posits spacetime emerges from vibrating strings in 10 or 11 dimensions, with AdS/CFT holography deriving gravity in anti-de Sitter space from conformal field theory on its boundary, implying emergent spacetime from entanglement entropy S = (A/4 l_P²) via the Ryu-Takayanagi formula.

Causal dynamical triangulation and asymptotic safety explore non-perturbative renormalizability, while postquantum theories treat classical spacetime interacting stochastically with quantum matter. Black hole entropy S = A/(4 l_P²) and information paradoxes drive research, with entanglement proposed as spacetime's "glue," potentially resolving ultraviolet divergences and unifying forces.

Criticism and opposition

From its inception, spacetime faced vehement opposition, blending scientific, philosophical, and ideological critiques. Historically, special relativity's denial of absolute space-time clashed with Newtonian intuitions and ether theories. Philipp Lenard, a Nobel laureate, derided it as "Jewish physics" in 1920s Germany, fueling anti-Semitic campaigns; the 1931 anthology Hundred Authors Against Einstein compiled rejections from figures like Ernst Gehrcke and Ludwik Silberstein, who disputed light-speed invariance and simultaneity. Pierre Duhem philosophically rejected it for severing ties to common-sense continuity, while Dayton Miller's flawed ether-drift experiments (1920s) claimed to refute null results. British physicists like Oliver Lodge resisted until the 1920s, viewing it as undermining ether; French and American academia lagged, with Nobel committees hesitating on relativity nominations until 1921 (for photoelectric effect).

Institutions like the Prussian Academy initially marginalized Einstein amid priority disputes with Poincaré and Lorentz. Soviet physicists under dialectical materialism critiqued it as idealist in the 1920s-1930s, though Lenin's heirs later accommodated it.

Contemporary criticisms focus on quantum incompatibilities: Sabine Hossenfelder argues spacetime's smoothness fails at Planck scales, embarrassing general relativity's quantum marriage. Lee Smolin rejects the "block universe" as timeless illusion, advocating evolving laws in Time Reborn (2013). Fringe voices like Myron W. Evans propose alternative geometries, but mainstream concerns center on emergent spacetime—Quanta Magazine (2024) deems it "doomed" as fundamental, with string theory's extra dimensions and LQG's discreteness challenging continuity. Postquantum classical spacetime, per Jonathan Oppenheim, posits stochastic gravity without quantization, testable via decoherence-diffusion trade-offs by 2025 experiments.

Philosophically, the "problem of time" and underdetermination in tests (e.g., Peebles 2017) question empirical uniqueness, yet no viable alternative displaces relativity's predictions.

Applications and implications

Spacetime concepts underpin technologies like GPS, which corrects for both special relativistic time dilation in orbiting satellites and general relativistic gravitational redshift. In particle accelerators, relativistic effects are crucial for high-energy collisions.

Cosmologically, spacetime's evolution traces the universe from the hot Big Bang to potential heat death or Big Crunch, depending on density parameters. The horizon problem and flatness problem led to inflationary models, proposing rapid early expansion smoothing spacetime.

Philosophically, spacetime challenges determinism and locality, with relativity implying no absolute simultaneity and quantum extensions suggesting non-local correlations, though preserving causality.

See also

- Quantum Physics

- Schumann Resonance

- Observer Effect

- Large Hadron Collider

- Higgs Boson

- Special relativity

- General relativity

- Minkowski space

- Four-dimensional space

Categories

This page falls under the following thematic categories based on its core subject matter in physics:

- Relativity and gravitation

- Mathematical physics and geometry

- Cosmology and astrophysics

- Quantum gravity and unification theories

- Black holes and compact objects

- Theoretical constructs and hypotheses